SGH has been attending the Hastings Housing Strategy steering group for the last 10 months. With co-writers Grace L and Ethan, they highlight fundamental issues with the Strategy, and ask just how useful is an ‘even-handed’ approach to tenants and landlords while we’re in a housing crisis directly caused by landlording?

Featured artwork by Chris Sav @disappointman. This article is the shortened, print version of a more comprehensive longread.

I was not aware of the Housing Strategy. It felt like chance that I stumbled into it. And people who know me would say I am categorically interested in housing. I’ve literally walked the country dressed as a house, and done a marathon, both to raise funds for my housing co-op. So herein lies the first problem: if it’s even beyond an activist’s awareness, who actually has the time or inclination to engage with the finer details of council planning?

Last year, at a meeting for local organisations, charities and activists (under the Hastings Housing Alliance), the lead housing officer at the council, Chris Hancock, announced that there will be a new Hastings Housing Strategy – in case people wanted some input. ”It’s all on the council website for anybody who’s interested,” he said.

Some people were interested, some (like me) even volunteered to join a new steering group to help draft the strategy. But seeing the few among us that could devote the time only begged the question we should all be asking: how is this strategy going to be representative of the people impacted by it the most – tenants – when there’s not many people who can realistically have a say in it?

Steering begins

A few weeks after the Housing Alliance meeting I arrived at council HQ. A mass of us were hurried up the stairs into the main council chamber. The place was heaving and a distinct tension hung in the air. There were three areas of crisis to choose from, and I was told to take my pick by a staff member. It’s like the shittest choose your own adventure game: there’s Private Rental Sector (PRS), Housing Supply, and Homelessness.

As I sat down, I immediately recognised a local letting agent whose shop window has a habit of breaking. Beside him were two members of Acorn Community Union, in their infamous red t-shirts, ferociously scribbling post-it notes with housing policy agreed on by union members a few nights previous. I’m an Acorn member too, but sit on the strategy group representing Hastings Rental Health Housing Co-op. The letting agent glanced from side to side uneasily, shifted in his chair, shifted again, like he can’t quite get his backside comfortable enough after this strange new dynamic shift.

We’re given an introduction by Chris Hancock about the state of affairs, most of which I know as a housing campaigner, but some of the statistics lay things eye-wateringly bare:

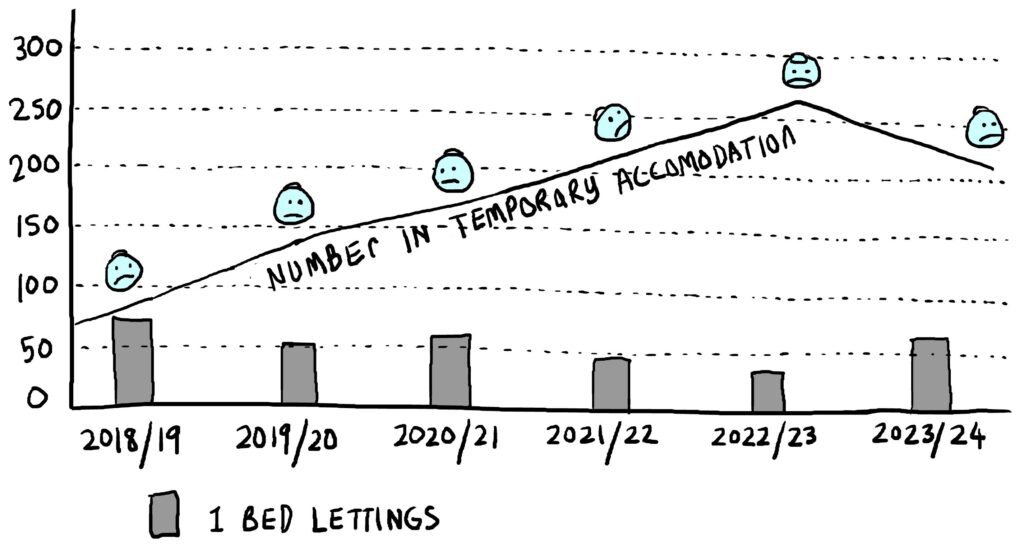

HBC is spending a third of their ENTIRE yearly budget on temporary accommodation to house people that have been made homeless by their landlords. That’s £7.8 million in the last year. This while landlords and letting agents continue to increase prices dramatically beyond what is affordable, up 37.8% since 2016. The South East also has the second highest number of second homes, even higher than London. And rough sleeping figures have increased more rapidly in Hastings than the national average. I looked around for a response from the landlords and letting agents in the room. No-one flinched.

The phrase “housing providers” gets bandied about a lot. That and “things have to work for both tenants and landlords,” an idea that came up so much that it’s now front and centre of the draft Housing Strategy. As one fellow campaigner astutely highlights: it’s like saying the field needs to work for both the sheep and the wolves.

Community solutions

What have I been up to for most of the last year? Mainly arguing for more support and funding for housing co-ops. Our government has not scrapped Right to Buy as promised but merely drawn out the time before someone can buy their social housing (effectively turning it into an inheritance game), so building more council or social housing is a false economy. It’s pretty widely understood that social and council housing is constantly mismanaged. And you simply can’t trust private developers and landlords to build affordable housing, it really is like getting inside the wolf’s mouth and impaling yourself on his teeth to help him chew you. What we need are homes created, owned and managed by the community – hence, housing co-ops.

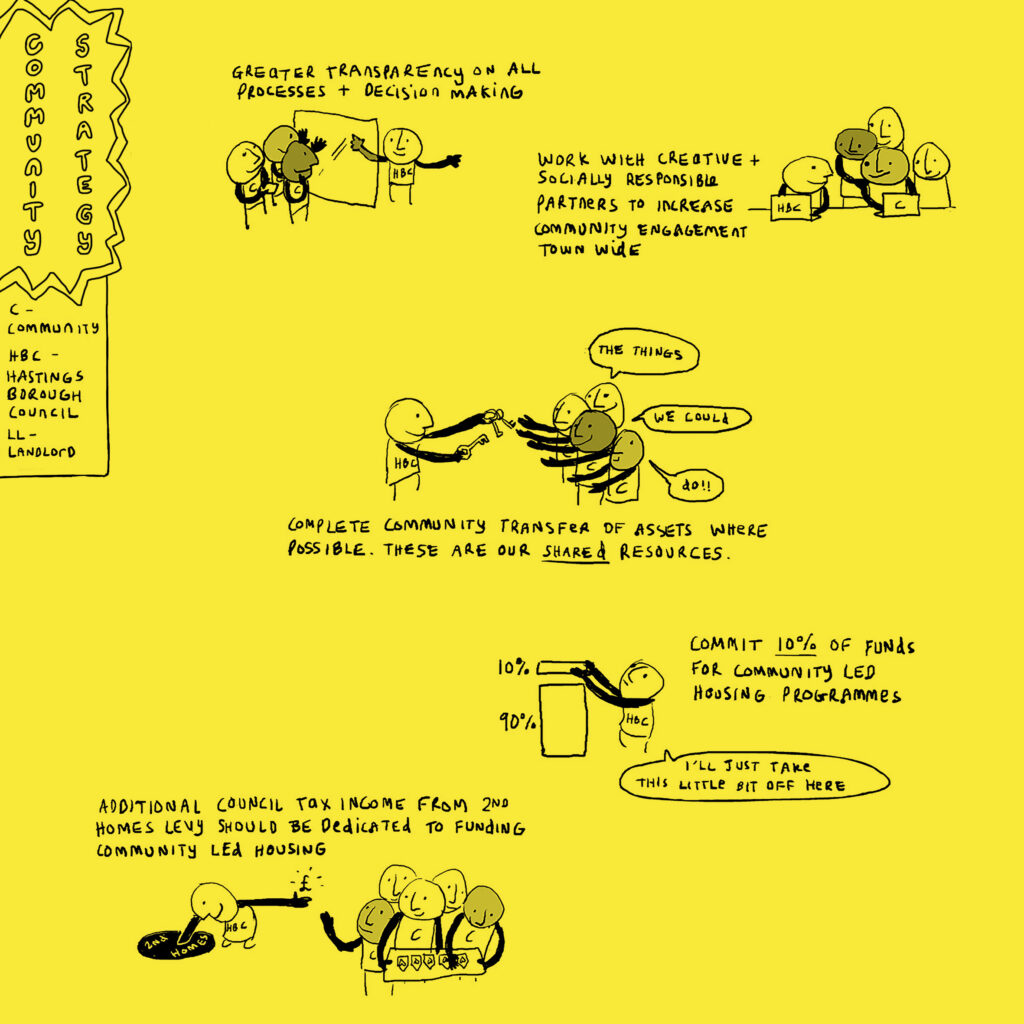

After the initial four meetings of slide show explainers, presentation speak and ground rules, we finally got into the meat of things in the working groups. I went along to Housing Supply. To my surprise, we were asked for more specific policies around community-led housing, and after some skirting around, Dawn Dublin of Black Butterfly just said it, “put 10% of HBC’s housing budget towards community-led housing.” That’s it! I shouted way too loud. That is how we get things moving, and take back control of this manic housing market.

We then spent much of these meetings having to drown out the patronising, underhanded ‘but you can’t meet demand on the scale developers can’. In particular this comes from a self-proclaimed housing enthusiast, who we later look into. No surprises here, he’s also a property developer. A quick search shows a slick development in Ashford, where you can rent a one bed flat for over £1000pm. Look out Hastings.

What the Hex Does This Housing Strategy Say?

Hastings Council has finally published its draft version of the strategy. Rejoice renters we’re saved!! Aren’t we?

The strategy puts forward laudable aims but might be doomed to fail in its stated goal that all the people of Hastings have “safe, settled and affordable housing”. Why? It claims to provide “a shared vision and framework for the council, housing providers, (both private and social), developers, support services, and community partners”. But according to the strategy itself, the main cause of homelessness is people being evicted from private properties because they can’t afford rent, or because their homes are being converted to holiday lets. So, in what way do landlords and developers share the goal of “safe, settled and affordable housing”? This is just one of the contradictions that plague the whole strategy.

The council is legally bound to provide housing for people who are homeless – but it’s clear that their interests are not always the same as those of residents. For example, the housing strategy involves forcing homeless households into new, private tenancies rather than offering them social housing – which might get people out of temporary accommodation quicker, but will do nothing to help families stuck in a cycle of insecurity CAUSED by renting in the private sector.

Hastings has been buying and refurbishing run-down accommodation from social landlords like Southern Housing to create cheaper temporary housing options for the council. But these homes aren’t replaced once they’re sold. The waiting list just gets longer. It is Southern’s one and only purpose to maintain social properties in order to permanently house people from the housing list; they’re not supposed to sell them off as temporary accommodation for people waiting on that list.

If the housing strategy was genuinely aimed at providing secure, safe, affordable homes for all, it would have to start with some recognition of the obvious: that the only secure tenancies are social tenancies run by well-managed councils and housing associations (if any in fact exist) and co-ops. A private landlord might be a nice person but they can still raise your rent at any time, evict you at any time for no real reason, and sell your ‘home’ without any consultation with you.

The strategy acknowledges that private landlords have no incentive to bring older housing up to modern standards of insulation and energy efficiency to tackle the health impacts of damp and mould. But it’s still the strategy’s aim is to expand the supply of private rented homes in the town and lobby the government to give landlords yet more public money to retrofit, and thereby increase the value of their private assets. This makes no sense.

Public solutions to private problems

The strategy doesn’t shy away from grand ambitions but in the end it provides no real vision for how to achieve them. The sustainable way to resolve its contradictions is to promote public investment to buy up, retrofit and refurbish our existing housing stock and convert the luxury assets of the rich – the hundreds of second homes and private rentals in the town – into safe, secure, social or co-operative housing as a basic right for everyone.

The council has some funding and powers it can use to provide secure housing itself, but it also has regulatory, planning and lobbying leverage that it can use to pressure other organisations and encourage a shift in government policy and funding priorities. Why not lobby Homes England and Southern Housing NOT to demolish the 400 social housing flats in Four Courts and to refurbish them instead, which would be much more environmentally sustainable and retain much needed social housing? Similarly with the planned demolition of Clifton Court by Hastings station.

The strategy talks about supporting private developers to build more housing. But why not just STOP selling off council land and property, and make it available for co-ops and community-led social housing developments that are truly sustainable, affordable housing? It also talks about lobbying for the Local Housing Allowance to be increased to cover rising private rents – an insatiable housing ransom. Lobby the government to cap those rents instead.

There are many examples to take from more pragmatic councils around the country. Will the proposed Landlords Charter have a “Clear and fair rent review or setting process” as Greater Manchester’s Landlords Charter has? Why not use capital funds to support Community Land Trusts, as seen in Cornwall’s community-led housing strategy and development of affordable housing? Gwynedd council increased council tax premium on second homes from 100% to 150% in 2022.

The council can’t solve everything on their own, but they’re failing to recognise that private landlords, developers, and unaccountable social housing companies are not going to solve the crisis they have created.

Send your thoughts online via the council consultation. Read the draft here, and the summary of the draft here.

It seemed difficult to get across the importance of community-led housing to some of the strategy group, so SGH has illustrated it for them.